By Denise Moorehead

From an Interview with Sara West

It was 1978, and I was sitting at a table with a group of African-American coworkers at the old Western Electric Company near Boston talking about the role that Black pride and empowerment played in building stronger communities. I had just graduated from college and was interning at the company, which employed a number of Black managers and workers with well-paying jobs.

|

|

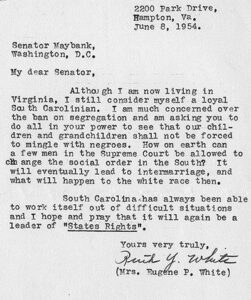

Students are encouraged to review primary source documents, such as this one. |

Nearly 50 years later, I still remember being dumbfounded when one of the women at the table – a woman at least 20 years my senior – said that it really didn’t matter, because at the end of the day “black people just aren’t as smart as white people. If we were, we’d be doing better.” More surprisingly, a couple of others at the table agreed.

When I countered with the contributions Blacks had made to the United States, the woman was genuinely surprised to learn about some of the educators, scientists, philosophers, businesspeople, etc. She was equally surprised by the large number of legal barriers that people of color and women had faced. She knew about slavery, but knew nothing about the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act, redlining, the denial of housing and other benefits to Black WWII veterans in the 1944 Servicemen’s Readjustment Act, and more.

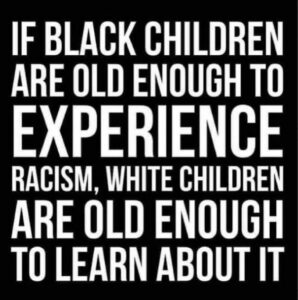

That’s when I realized how critical it is to teach inclusive history to students at every step of their educational journey. According to Professor Arlene Dávila, founding Director of the Latinx Project at New York University, research has shown that when underrepresented students learn about their history and culture, they perform better academically and graduate at higher rates.

Additionally, a May 2023 study by the Johns Hopkins Institute for Education Policy and UnidosUS study cites, “… other students benefit from learning about diverse groups of people.” The study found that widely used history textbooks omit seminal Latino events and contributions.

Whose Story? It Matters.

Whose Story? It Matters.

Sara West, who teaches Grade 5 history at Schools for Children’s Lesley Ellis School in Arlington, Mass., agrees that all children benefit from learning the parts of history that are too often omitted from most standard teaching materials. That’s why Sara and her colleagues at the school create, change, update and plan curricula that incorporate information and materials, including primary sources, that provide students with a richer understanding of “how America got to be America.”

Sara teaches history like a story. She believes it is more important for students to understand the story of the “places we are and our government and our country” – and their place in it than to remember a series of dates. She helps students engage in deeply interactive learning. When they have a “voice in their own learning,” they are more apt to make the connection between history and their lives and today’s world.

“The Zinn Education Project has created these really cool simulations,” Sarah shares. They give students the opportunity to role-play how they might have approached an issue in history and better understand the various, sometimes, competing aspects. For example, in the civil rights curriculum, Sarah explains that in order to lay the foundation for looking at the civil rights movement, “we need to talk about the history of slavery in America, cover the Civil War, and then we need to look to the gaps in our understanding.”

The period of Reconstruction is one of those gaps. Sarah shares that it is rarely and barely taught in most history textbooks. Her students use interactive learning to look at a series of questions that help them understand some of the issues that the country was facing in post-Civil War America. “We take a deep dive into what happened right after the Civil War,” states Sara.

For example, the students were tasked with determining what should be done with southern plantations. “There are all of these newly free people,” Sara explains. “Do they get to become landowners? Is the land given to them by the government to manage? Should the land be taken away from the plantation owners?” The class also considers what to do with the Confederate leaders. Should they be punished, should they be jailed? Students also discuss how they can ensure the safety of slaves. These are just a few of the issues that students must consider as they learn about Reconstruction.

Explaining the process students use to gain this understanding, Sara emphasizes that she provides historical context, supplements texts with primary sources and poses six specific questions for the students to answer. She asks them to think of themselves, “as a delegation of newly freed people going to Washington to make proposals on what our newly reformed country should look like.”

Providing Agency

Sara, however, leaves it to the students to decide what process they will use to create these proposals. She tells them, “This is your process. You have to decide among yourselves. You can’t be a fractured delegation; you have to be of one mind if you’re going to make these proposals.”

Sharing details from a 2023 class, Sara shares, “They chose to have a person be the speaker for each question. Using a speaking stick, they went around and had a really rigorous debate.”

The students considered what was fair and not fair for the newly freed people, the former plantation owners and the Confederate leaders. “And then they came to consensus on each of the six items and decided what they thought should happen,” Sara adds. “It took more than two class periods to do a Socratic circle round table debate that the students ran themselves. That led us to this great place of curiosity.” Then the group compared what they thought should happen with what actually happened in history.

In addition to role-play, Sara has students look at primary source documents. “I think that’s an important part of history, and there are so many ways to do that and have it feel interactive, she says. “We look at a lot of imagery, images of Jim Crow era life. We looked at images of a group of young black kids looking through a fence at a White’s-only park that they weren’t allowed to go play at, a picture of a young black girl and her grandparents standing in a store window looking at all-white mannequins.”

[The students] look at these primary source documents, and they reflect on them. Sara continues, “I ask them, ‘What do you see; what do you think it means; what questions do you have? What connections can you make about these images?’ We look at voter registration documents, journal entries by people who lived through that period …” Sara also shares primary source videos and then creates role-playing exercises to deepen students’ understanding of what they have watched.

Owners of Their Learning

Owners of Their Learning

Throughout the teaching-learning process, Sara helps students “make connections to what’s going on today.” She exposes students to current news clips to help them draw a line from what they are learning in history class to today’s events. For example, they discussed the expulsion of two young Black Tennessee state representatives and the Jim Crow and anti-Civil Rights era rhetoric that was used to justify expelling them – before a national outcry led to their reinstatement.

Similarly, the curriculum on immigration makes important connections within American history. Beginning with Columbus “discovering America,” students learn about the forced migration of Native American people as well as Africans. Students study the many waves of immigrants coming to the United States and what led them to leave their home countries. They are able to make connections to modern-day immigration, the difficult process of becoming a citizen, and today’s border and refugee crises.

Sara adds that as she teaches the Lesley Ellis civil rights and immigration curriculums, “I’m relearning it as I’m teaching the students, it’s forcing me to confront history in a new way, … and I’m really grateful for that.”

Calling that out … and looking at how that connects with this history that we’re learning really lights up the students,” Sara tells us. “They really get to become the owners of the learning.”